News & Insight

Thatchers v. Aldi: lookalike squeezed out by trade mark registration

“Lookalike” goods and services pose a dilemma to UK law, especially with the advent of AI. Too much regulation stifles competition; too little allows for parasitic behaviour like copycat packaging that in turn can have anti-competitive effects. The UK has no unfair competition law as such. Brand owners argue that that the UK’s trade marks registration, passing-off and consumer/business to business protection laws offer inadequate protection against parasitic trading notably by supermarkets.

With the January 2025 Court of Appeal decision in Thatchers v. Aldi, the tide may be turning, although Lord Justice Arnold, delivering the unanimous judgment of the Court, made clear that: “it is not the function of this Court to enter into these policy debates. Our task is to apply the law enacted by Parliament to the facts of this case”.

Thatchers

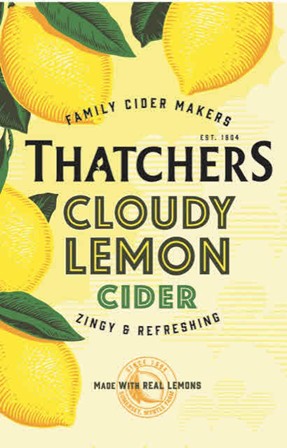

The facts of the case were that Thatchers own a UK trade mark registration covering “cider” for the 2-D device represented as follows:

Thatchers are a well-known and long-established UK producer of ciders, and in around 2020 decided to launch a new cider made with real lemons on the UK market under the THATCHERS CLOUDY LEMON CIDER DEVICE brand.

The device brand was deliberately designed by Thatchers to stand out on supermarket shelves since it was acknowledged that consumers only look at products like cider on a retailer’s shelf for a few seconds before deciding whether to buy.

The device brand was applied by Thatchers to their cans and to their four-pack packaging as shown below:

Thatchers mounted a substantial marketing campaign for their THATCHERS CLOUDY LEMON CIDER DEVICE product including on TV, outdoor billboards and posters, social media, in major cities and holiday destinations and at trade events, as a result of which they achieved millions of retail sales in litres and GBP. Around fifty per cent of those retail sales were supermarket sales.

Aldi

Aldi is a German-owned supermarket in the UK that specialises in own-brand products in order to keep prices down, a business model reflected in Aldi’s well-known advertising: “like brands, only cheaper”.

Since 2013, Aldi has sold cider under Aldi’s TAURUS brand (arguably a take-off of STRONGBOW).

In 2022 Aldi decided to launch a limited-time run of cloudy lemon cider under the TAURUS brand, “benchmarked” in quality and packaging to the THATCHERS CLOUDY LEMON CIDER DEVICE product, although for costs reasons using lemon flavouring rather than real lemons.

The evidence before the Court included, for example, an email from Aldi to an external design agency: “can we please see a hybrid of Taurus and Thatcher’s [sic] – i.e. a bit more playful – add lemons as Thatcher’s etc“.

This is what the Aldi same-size cans and packaging looked like:

Aldi’s cloudy lemon cider successfully sold out within a period of 10 months, apparently without any promotional spend.

IPEC

Thatchers sued Aldi in the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (“IPEC”) for registered trade marks infringement and passing off, and lost.

On the standard type of infringement, the IPEC judge held that there was no likelihood of confusion largely because of the dissimilarities between the brand names THATCHERS and TAURUS, other elements in the Thatchers trade mark and Aldi sign like lemons being descriptive and/or non-distinctive. This was even though the judge found that Thatchers had succeeded in proving enhanced distinctive character in the THATCHERS CLOUDY LEMON CIDER DEVICE trade mark overall. The passing-off claim similarly failed for lack of consumer deception.

Although the judge found that Thatchers enjoyed reputation in the THATCHERS CLOUDY LEMON CIDER DEVICE trade mark, and that the Thatchers mark would be brought to mind by the consumer on encountering the Aldi product, the judge found that the Aldi product neither took unfair advantage of, nor was detrimental to the distinctive character or repute of the Thatchers trade mark, so that the extended type of infringement was also not made out.

Thatchers appealed to the Court of Appeal against the IPEC judge’s decision on the extended type of infringement only.

Court of Appeal

Lord Justice Arnold reiterated the nine conditions for the extended type of infringement under Section 10(3) of the UK Trade Marks Act:

“(i) the trade mark must have a reputation in the UK; (ii) there must be use of a sign by a third party within the UK; (iii) the use must be in the course of trade; (iv) it must be without the consent of the proprietor of the trade mark; (v) it must be of a sign which is identical or similar to the trade mark; (vi) it must be in relation to goods or services; (vii) it must give rise to a “link” between the sign and the trade mark in the mind of the average consumer; (viii) it must give rise to one of three types of injury, that is to say, (a) unfair advantage being taken of the distinctive character or repute of the trade mark, (b) detriment to the distinctive character of the trade mark (often referred to as “dilution”) or (c) detriment to the repute of the trade mark (often referred to as “tarnishment”); and (ix) it must be without due cause.”

Conditions (vii) (link) and (viii) (a) (unfair advantage) and (c) (detriment to repute) were contentious, as were issues relating to the similarity of sign and trade mark.

Similarity of sign and mark

The IPEC judge compared the Aldi product – which the judge decided was the can alone – with the THATCHERS CLOUDY LEMON CIDER DEVICE trade mark as registered in 2-D form.

The Court of Appeal said that the IPEC judge was wrong on both counts.

First, the “sign” complained of was the trade dress of Aldi’s can and four-pack packaging.

Second, the correct comparison for infringement was between the sign and notional fair use of the registered trade mark. The way in which Thatchers used the mark, that is, on the Thatchers cans and four-pack packaging – was the paradigm example of notional fair use, and was also the basis for the assessment of distinctive character and reputation.

The correct comparison led to a higher degree of similarity between the sign and the registered trade mark than determined by the IPEC judge.

Link

The IPEC judge’s finding that consumers would make the requisite link between the Aldi product and the registered trade mark was supported inter alia by social media posts, and confirmed by the Court of Appeal.

Intention

The defendant’s intention can be relevant to assessing whether the damage to the registered trade mark envisaged by the extended type of infringement is made out, in the words of Lord Justice Arnold “[t]he rationale for this is that an experienced trader like Aldi is presumed to understand its target market and therefore to know how the consumers in that market are likely to react”.

The IPEC judge was swayed by Aldi’s evidence that the Aldi product should be understood as a TAURUS branded-style product. Whilst relevant to intention to deceive under the standard type of infringement, this was much less relevant to an intention to take unfair advantage of the reputation of the registered trade mark.

Further, the IPEC judge (as mentioned above) had misjudged the similarities in the sign and mark, like the lemons and pale-yellow background, which showed that the Aldi product departed significantly from Aldi’s TAURUS brand styling.

Lord Justice Arnold considered significant Aldi’s reproduction of the pale-yellow horizontal lines in the registered trade mark: “it is often the reproduction of inessential details which gives away copying. The judge was correct to say that this is not a copyright or design case, but what this shows is close imitation by Black Eye of the Trade Mark: there is no other explanation for it in the evidence.”

In reassessing Aldi’s intention, Court of Appeal concluded that the close resemblance between the sign and registered trade mark, and the sign’s design history indicated that whilst Aldi did not seek to confuse consumers as to the origin of their product, Aldi did intend to convey to consumers the message that: “the Aldi Product was like the Thatchers Product, only cheaper”.

To that extent, Aldi had intended to take advantage of the reputation of the Thatchers registered trade mark in order to assist Aldi in selling their product.

Unfair advantage

The Aldi product achieved significant sales with no promotion expenditure.

That coupled with the above, led the Court of Appeal to overturn the IPEC judge’s finding that Aldi had not taken unfair advantage of the reputation of the Thatchers trade mark.

This was a clear case of “a transfer of the image of the mark” and “riding on the coat-tails of that mark” for which there was no due cause.

Damage to repute

The Court of Appeal, however, dismissed Thatchers’ appeal against the IPEC judge’s determination that Aldi’s use was not detrimental to the reputation of the registered trade mark.

In short, the consumer would realise that the Aldi product was not made with real lemons and that this difference likely contributed to the cheaper price.

Descriptive use defence

Finally, Lord Justice Arnold determined that Aldi could not rely on the descriptive use defence to infringement. The sign as a whole including the lemons and so on, was distinctive of Aldi and did not describe the characteristics of the goods (other than, the Aldi product is like the Thatchers product only cheaper).

Also, Aldi’s parasitic use was not in accordance with honest practices in industry and commerce because it was unfair competition.

Concluding thoughts

The take from this decision (subject to any appeal to the UK Supreme Court) is that the registration of trade marks can in certain circumstances protect against unfair competition in the form of parasitic trading.

Signs that can be registered as trade marks in the UK and EU cover many modern promotional means used in real and digital environments like logos, 3-D shapes and characters, music and other sounds, holograms, moving images and multimedia.

This piece was contributed by Robert Humphreys and Tristan Morse. Do please reach out to a member of the team if you would like to discuss matters relating to intellectual property or commercial law generally.

All the thoughts and commentary that HLaw publishes on this website, including those set out above, are subject to the terms and conditions of use of this website. None of the above constitutes legal advice and is not to be relied upon. Much of the above will no doubt fall out of date and conflict with future law and practice one day. None of the above should be relied upon. Always seek your own independent professional advice.

Humphreys Law

If you would like to contact a member of our team, please get in touch by filling in the form below.

"*" indicates required fields

Humphreys Law