News & Insight

Contact tracing app launches: download for victory (but 5 legal issues to consider) …

The innovative arm of the NHS, the NHSX, has launched an in-house-developed contact tracing mobile application to help stop the spread of COVID-19.

The app is being launched as part of the UK’s ‘Test, Track and Trace’ strategy, which the NHS hopes will lead the path out of lockdown here.

The population of the Isle of Wight will be the first to trial the app. If it goes well, expect it to be rolled out to the rest of the UK.

60% of British population will need to voluntarily download the app for it to make an impact. Taking into account statistics on the penetration rate of the popular messenger app WhatsApp in the UK, 58% of those surveyed, it would seem NHSX has its work cut out to get 60% of the British population on board.

How does the app work?

A contact tracing app is designed to let people know if they have been in close proximity with someone who later tests positive with COVID-19. The concept is simple – users download the app onto their phone, which runs in the background. It continuously uses Bluetooth signals to perform a ‘digital handshake’ with the phones they come into close contact with. All this data is stored anonymously. If someone then later becomes sick with COVID-19, the user will receive a notification on their phone to let them know they have been in close contact with a patient in the last 28 days.

NHSX has said the data will not be held for more than 28 days and the app will be deleted once the pandemic is over. Currently, the app runs solely on Bluetooth signals, and is unable to track any location data on any of the users’ phones.

Centralised v decentralised model

The NHSX has come under pressure for rolling out their own contact tracing app – which works on a centralised model.

Under a centralised model, the data collected is held centrally on the NHS’ server. If anyone is then to fall sick with COVID-19, the alerts sent to those who have come into close contact with these individuals will also come from the NHS server.

The main issue under a centralised model is that it puts the servers in a position of trust, where we trust that our data will not be misused.

Under a centralised system, sick users will not only report their symptoms, but also hand over their anonymous data. The government has argued this anonymous data will be key to allow it to understand how the disease appears to be spreading whilst respecting the user’s privacy.

The NHSX has pushed for a centralised system because of the apparent benefits it can bring to the public health sector. The technical director of the National Cyber Security Centre (NSCC), Dr Levy explained under a centralised system, the NHSX could use the data collected to create anonymous contact graphs to analyse, which could show where the disease appears to be spreading and pick up any useful behaviour of how the disease spreads.

UK rejects decentralised model (for now)

The UK is one of the few European countries who have rejected the contact tracing app developed by Apple and Google. The two tech titans have been collaborating on creating an API that would also use Bluetooth signals to track the spread of COVID-19.

The Google/Apple version works on a decentralised model, where no data is stored on servers. Alerts are sent between the phones whose users are sick and those who have come into close contact with them. Various EU bodies and efforts have been advocating for a decentralised approach. Experts have been pushing for a decentralised model as it can put “hard technical limits on surveillance abuses” not possible under the centralised approach.

Concerned about how Orwellian this sounds? You’re not alone.

In an online survey conducted by HLaw client Auspex International, it found that only 16.7% of those surveyed were comfortable with any kind of monitoring of personal data. We’ll leave you to decide how you feel on the Orwellian front… whilst we take a deep dive into the topic five legal issues to consider with contact tracing apps.

1- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

How anonymous is the data collected by the app? Anonymised data does not fall under the GDPR per se.

Nevertheless, pseudonymised data, where the processing of personal data has been cleansed to remove any personal data attributed to a specific data subject is still considered personal data under the GDPR.

The government argues that all data collected will be anonymous. It will only take the first half of the user’s postcode and the model of the smartphone they use.

It will be interesting to see if that theory holds water in practice. In a 2019 study, researchers found that they could re-identify 99.98% of individuals in anonymised data sets with just 15 demographic attributes.

Earlier in April, the European Data Board stressed the importance of publishing data protection impact assessments (DPIAs) in the context of contact tracing apps. Under the GDPR, a DPIA is required for data processing that is “likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of data subjects.” The DPIA should set out the fair processing notice, purpose limitations, outline who the controller is, examine what data is collected and how is it stored.

Only a handful of these questions have been answered in relation to the new app, and where to find the answers has not been made clear to the public either. The DPIA has yet to be published, despite the app now being live (in the Isle of Wight).

Matt Hancock, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, has confirmed that no legislation will be introduced to govern the security, privacy and data concerns this app may bring. This is because the app is not mandatory to download, and citizens can choose not to use it.

2- Human rights under ECHR

We have followed the first case heard in British courts on the police-use of automatic facial recognition tech.

The claimant argued there had been a breach of his Article 8 rights, his right to respect for a private and family life. The Court disagreed in its judgment and said that police-use of the tech was in the public interest.

The government may find itself fielding analogous claims that the app acts incompatibly with Article 8 of the ECHR due to concerns the data will be held and used against individuals post pandemic.

The app must also abide by Article 11 of the ECHR, which is the respect of one’s freedom of assembly and association. Data collected by the app has the potential to be mapped out to investigate whether people have been breaching social isolation rules.

The government may struggle to use the data collected by the app to police whether people are truly self-isolating and staying at home.

3- Where’s the data?

The UK has gone down the centralised model of handling and holding the data.

There seems to be no information on how this data will be encrypted and uploaded to the central NHSX servers.

4- Sale of data

Although the NHSX has promised to shut down the app as soon as the pandemic is over, the chief executive of the NHSX Matthew Gould admitted citizens could not ask for their anonymised data to be deleted at a later date, as it would be useful for “research”. He further said that data collected by the app should be made accessible to organisations who needed the data for “public health purposes”.

If such personal data was to be leaked to the private sectors, the consequences could be far reaching.

Our data could be sold to insurance companies, affecting the way we purchase life, health and car insurance… Gattaca much, anyone?

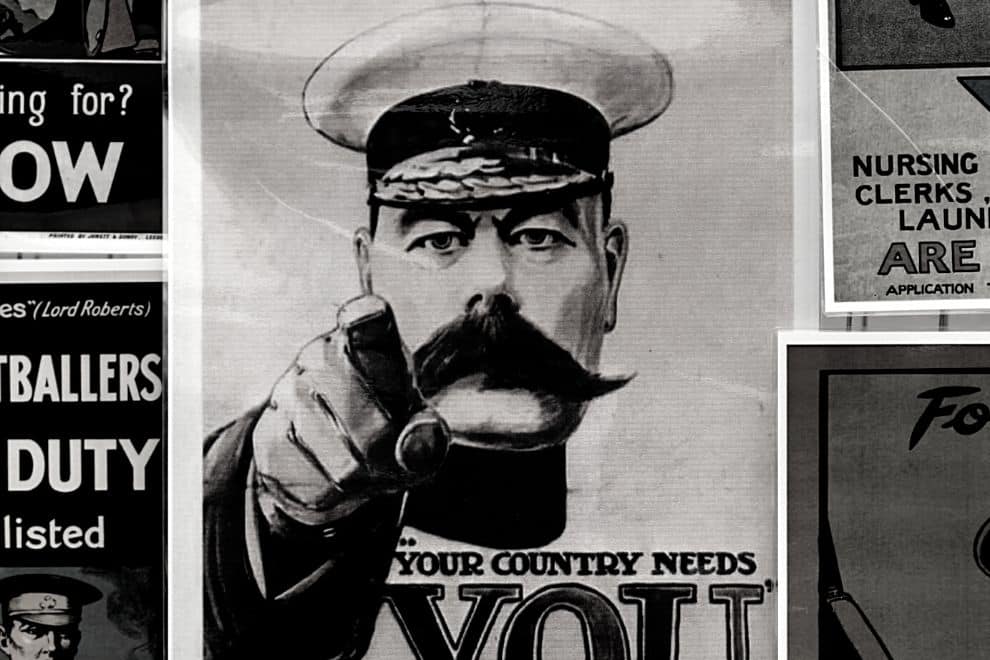

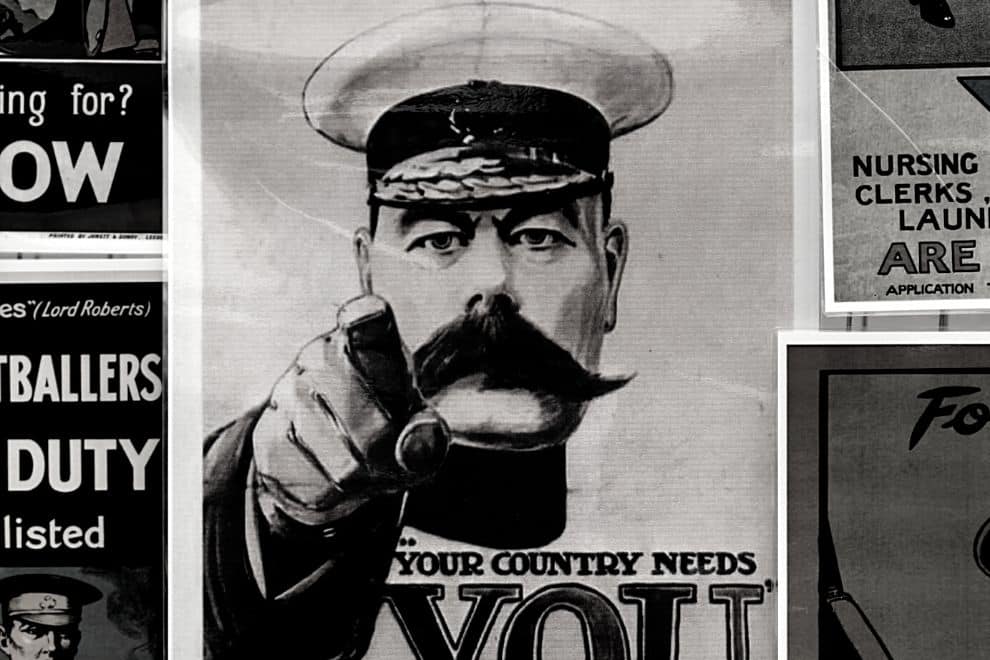

Would us responding to our “civic duties” by using the app come back and bite us later on? All we can hope is that the legislation will be put in place to ensure nothing of this nature happens.

5- Employment law / discrimination

Employers seem to be looking to roll out their own contact tracing. Big four firm PwC has developed its own app to get the ball rolling for their plan to get employees back into the office. They have promised not to share the data with public health officials but will be looking to make the app mandatory for all their employees.

Employers also have a duty to protect the health, safety and welfare of their employees under the Health and Safety Information for Employees Regulations 1989. Questions arise when employers should be making the call to allow employees back into the workspace. Employees could bring their employers to the employment tribunal if they negligently allow their employees back into the work place where they end up contracting COVID-19.

Final thoughts, for now…

The NHSX and the government should receive some recognition for working around the clock to ensure the privacy and data concerns are being evaluated and considered as they develop the app.

But even a few months ago going live with a project of this scale, at this space and with this level of room for technical error would have been unthinkable. Privacy campaigners will no doubt be watching very closely that the rush to exit lockdown will not push through restrictions on our civil rights that will be difficult to reverse when the dust settles.

This piece was researched and prepared by Victoria Clement.

All the thoughts and commentary that HLaw publishes on this website, including those set out above, are subject to the terms and conditions of use of this website. None of the above constitutes legal advice. Much of the above will no doubt fall out of date and conflict with future law and practice one day. None of the above should be relied upon. Always seek your own independent professional advice.

Humphreys Law

If you would like to contact a member of our team, please get in touch by filling in the form below.

"*" indicates required fields

Humphreys Law